(Notes 2) CompSci 677 Distributed System - Editting

Disclaimer: This is my personal class notes for Distributed Operating System course taught at UMass Amherst. All images are taken from the free version of textbook and from slides. Notes contains extracts from textbook and from slides. This notes are for me to review the materials and for you if you are looking to review some concepts.

Lecture 7 Remote Method Invocation

Lightweight RPC

We don’t need to create RPC to send request to another process on the same physical server -> lightweight RPC. The optimization is to construct the message as a buffer and simply write to the shared memory region:

- No need for marshalling

- Get rid of explicit message passing completely. Rather shared memory is used as a way of communication

- Stub uses run-time flag to decide whether to use TCP/IP or shared memory

- No XDR needed

Other types of RPC

Asynchronous RPC:

- Client is not blocked after making an RPC call: it sends the request, waits for an acknowledgement then resumes its own execution

- Request reply behavior often not needed

- Server can reply as soon as request is received and execute procedure later

Deferred Synchronous RPC:

- Same as Asynchronous RPC, but the server returns the result by via an asynchronous RPC.

- The difference with this and asynchronous RPC is that the results is sent back via asynchronous RPC, so the client just need to send an acks to the server after receiving the results.

One way RPC:

- Same as Asynchronous RPC, different in that client doesn’t even wait for an ACK from server

- Limitation: doesn’t guarantee reliability

Remote Method Invocation

RMIs are RPCs in Object Oriented Programming Mode, i.e., they can call the methods of the objects (instances of a class) which are residing on a remote machine.

RMIs support system-wide object references, i.e., parameters can be passed as object references here, which is not possible in normal RPC.

Q: What is binding?

A: A Process in which a client links to server that have implementation for the process.

When a client binds to a distributed object, the client stub (proxy) loads the interfaces into the client address space.

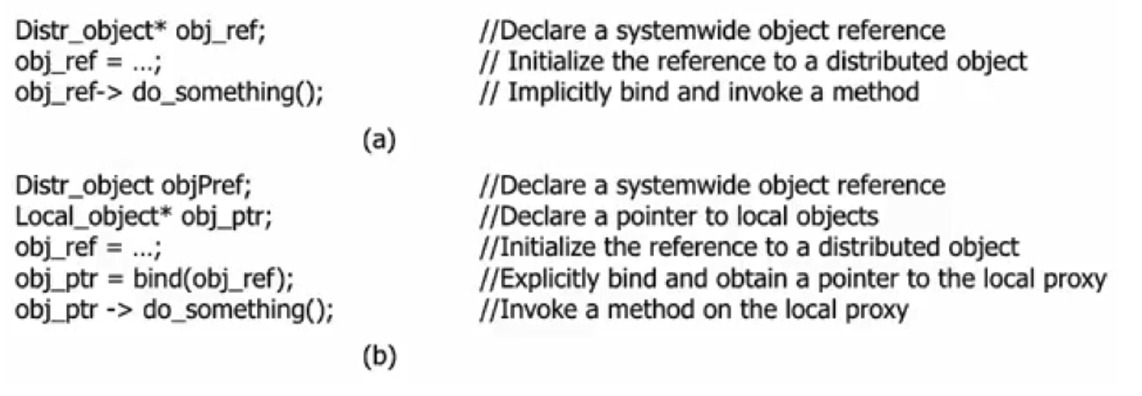

(a) Implicit binding uses just global references, and it is figured out on run-time that it is a remote call (by the client stub)

(b) Explicit Binding uses both global and local reference. Client explicitly calls a bind function before invoking the methods.

Parameter Passing

Passing a reference to an object means passing a pointer to its memory address over the network. Local objects are passed by value, and remote objects are passed by reference.

Java supports monitors, which are synchronized objects.

For synchronization, lock has to be applied on object which is distributed amongst the clients. How to implement distributed lock?

- Lock at the server: clients will make requests to the server, where they will contend for the lock and will be blocked. Problem: what if the client crashes while blocked?

- Lock at the client (proxy) collectively: need some protocol which decides which client will get the lock and the rest will be blocked (waiting for the lock).

- Java uses proxies for locking: No protection for simultaneous access from different clients, applications need to implement distributed locking.

Reference: Hello World Java RMI

Reference: Concurrency in Java RMI

Message Passing Interface (MPI)

MPI is a higher level programming abstraction than sockets.

Question: Suppose that you want to implement a client-server system. There are multiple clients and one server. The server is stateful and the state is updated based on the requests from the clients. A simple example would be a server that stores a counter that is incremented every time any client sends a request. Consider the RPC and RMI mechanisms. Assume that remote procedures/objects cannot to store state outside of the procedure/object itself (for example, they do not have access to the file system of the server).

(a) Can you use RPC to implement the system? Why or why not?

(b) Can you use RMI to implement the system? Why or why not?

Answer:

(a) No. Regular RPCs cannot be used to implement stateful servers without access to the file system. Remote procedures cannot use global variables so they can only operate on constants and the input parameters provided by the clients. The server will not be able to keep a counter across requests from different clients.

(b) Yes. RMI can be used to implement the system. Client can invoke on the remote object to increment the counter.

Lecture 8: Persistency, Message Queueing System and Streaming

Persistence and Synchronicity

Persistency: messages are stored until receivers are ready. Examples: email

Transient: messages are stored so long as sending/receiving processes are exeucting. Discard message if it can’t be delivered Exampls: Transport-level communication (TCP/UDP, sockets), Network-level communication (IP)

Asynchronous communication: Sender resumes execution immediately after it has submitted the message. Need a local buffer at the sending host.

Synchronous communication: Sender blocks until receives acknowledgement from receiving host. When?

- Receipt-based: receiving host acks when maesage stored in a local buffer

- Delivery-based: receiving host acks when message delivered to receiving process

- Response-based: receiving host acks when message processed by receiving process

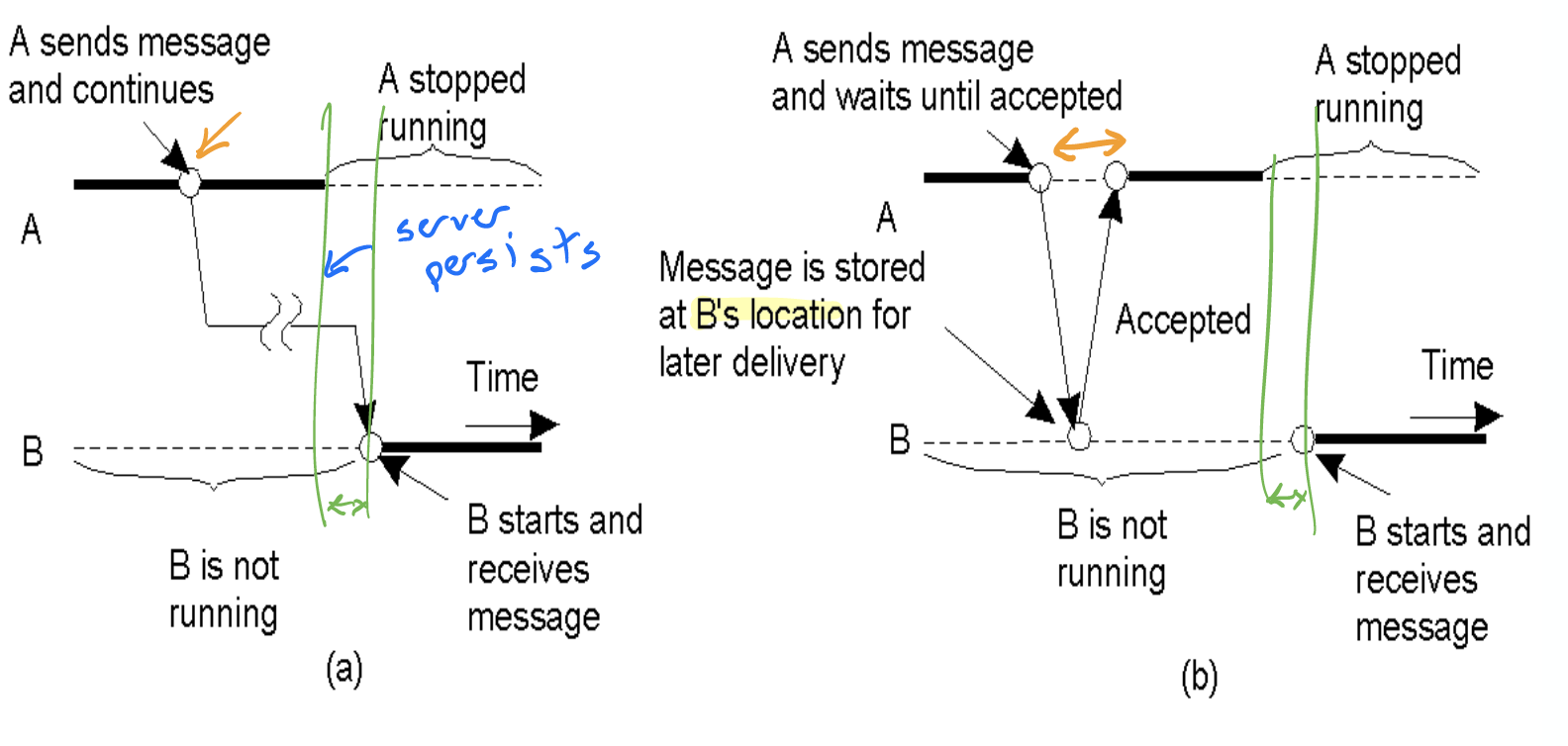

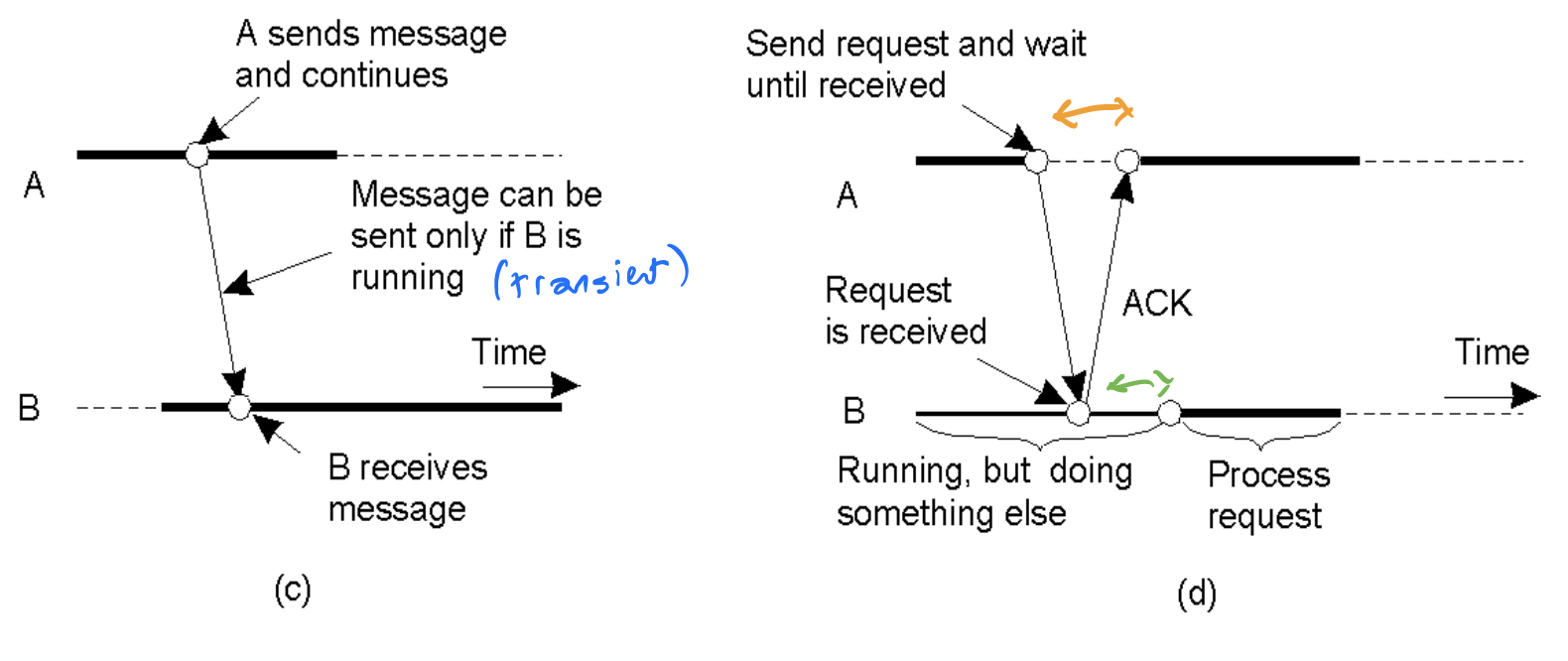

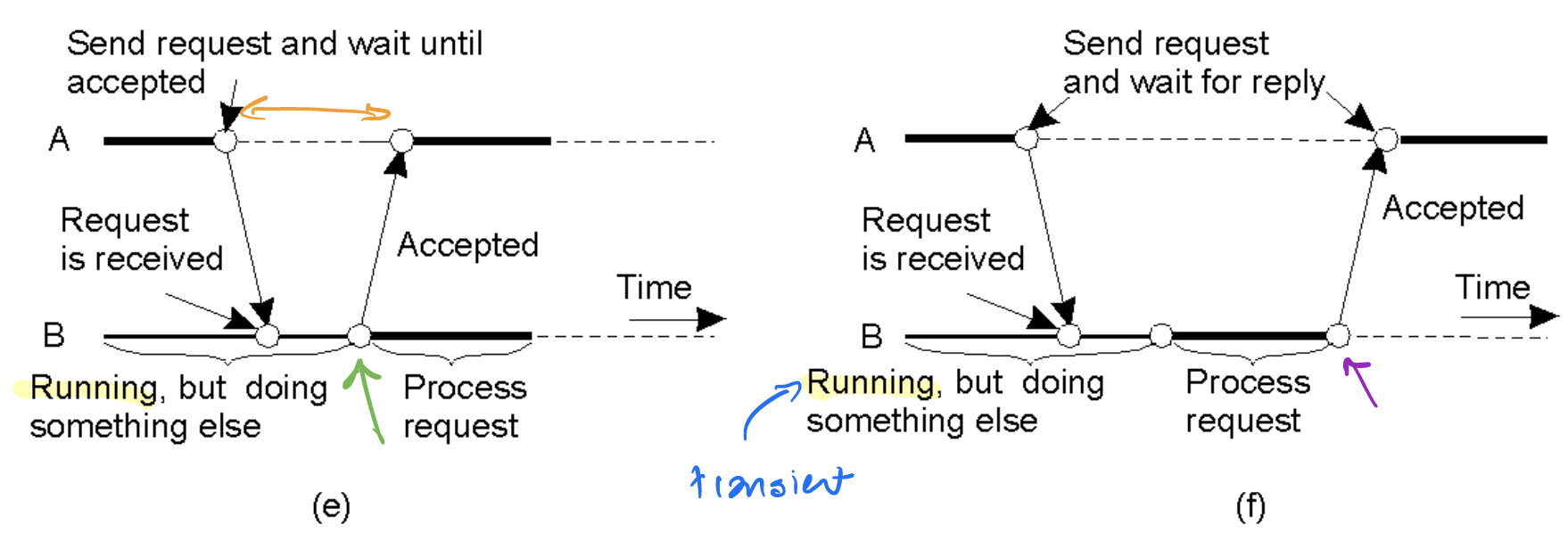

Six combinations of persistence and synchronicity

(a) Persistent asynchronous communication (b) Persistent synchronous communication

(c) Transient asynchronous communication (UDP) (d) Receipt-based transient synchronous communication

(e) Delivery-based transient synchronous communication (asynchronous RPC) (f) Response-based transient synchronous communication (RPC)

Message Queueing System

Supports Persistent Assynchronous Communication. Uses on-disk buffers to ensure persistence of messages over long periods of time. Persistence don’t guarantees when or if the message will be delivered or read, it only ensures delivery.

Example: Kafka, RabbitMQ, ActiveMQ, ZeroMQ, etc.

Abstractions: get, put, poll (non-blocking), notify (also non-blocking)

Queue manager interacts with application

MQS routers (also called relays) provides persistence queueing.

Message Brokers - application level programs that take messages from queues and transforms it so that they can be understood by destination. This is also used by publisher-subscriber systems, where a queue actually acts like mailing list - having multipler receivers and the sender doesn’t know who the message will be delivered to.

Stream Oriented Communication

isochronous comunication

Server-push based: Clients start receiving data without it being requested.

Subjected to Timing Constraints.

Playback freezes if data is not delivered on time, affected the streaming experience.

If we wish to watch 30fps, a frame needs to come in every 33ms. Thus, end-to-end delay cannot be arbitrary, and must have an upper bound.

Quality of Service

QoS is a way to encode the requirements of audio and video stream.

Maximum end-to-end delay bound: Need to be fixed to avoid playback glitches

Jitter: The fluction in the delay is jittler. We want to minimize jitter to ensure a steady data rate

Loss: Refers to the loss in data packets. With TCP, loss is handled using re-transmission. In video streamming, retransmission may not be an option. Late data might be as good as no data for live streaming.

Token Bucket

An OS-based method for enforcing QoS.

Two parameters: R and B

Tokens are added to the bucket at a constant rate R.

Every time, a packet needs to be sent, it needs to grab a token that will be generated by the OS. The OS will generate tokens at a steady rate R. R is the bandwidth that needs to be guaranteed.

B is depth of the bucket or the maximum number of packets that can arrive simulatanenously. If a token arrives when the bucket is full, it is discarded.

We want to reduce playback glitches in video streaming. Packets may have jitter because each will arrive at a different time, even though we sent them in steady gaps. To paly at a constant fps f, we need to play the next frame in 1/f seconds. But after frame 1 arrives, frame 2 haven’t arrived in that time difference, hence resulting in playback glitch. One way is to hold the packets in the buffers at the receiver before starting playback. Hopefully, if data continues to arrive at a good rate, our buffer will always have data and we can keep playing. To deal with packet loss, use interleaving (sending packets in an interleaving order) or Forward Error Correction (data redundancy).

Q: UDP is inherently better suited for streaming. Why?

A: TCP is server-pull based, so client needs to continuously contact the server to pull the data. But almost all streaming occurs over HTTP (and TCP) due to the universal availability of HTTP.

Lecture 9: Naming

When you type www.cnn.com in the browser, the browser will do name/url lookup in DNS, which maps that name to the IP address of the machine, which will then be used to create a HTTP connection to that machine. This process is known as name resolution.

Approaches to naming: Hash-based vs Hierarchical

Distributed Hash Table

Consistent Hashing:

- Map node IDs to value in [0, n). Use uniform distribution for mapping (hash)

- Maps keys to values in [0. n)

- Data item with key k is stored in the smallest node with id >= k

- Node joins: take <k, v> pairs from successor

- Node leaves: give <k, v> pairs to successor

Chord algorithm: a p2p system where each node store object, we use a distributed hash table to locate the object - the idea of consistent hashing.

- Each node keeps a finger table of size log(n).

- Lookup takes O(log(n)) hops

Hierarchical Naming - Domain Name System (DNS)

DNS can be seen as a large distributed database that does key-value lookups. The key is machine name and the value is IP address.

DNS is distributed through three logical layers:

- Global layer, highest level nodes and the root of hierarchy, mostly static

- Administrational layer: organization that are part of each of the domain

- Managerial layer: lowest layer, are actual nodes, where there are frequent changes

Two ways to do name resolution in DNS: iteratively and recursively.

Iterative: clients iteratively look for domain name servers of each of the levels of hierarchy. Once clients reach the final machine name, clients get the IP address. Client can cache requests that have been resolved at local machine on the local name server.

Recursive: Clients make only one request on the root server, and the root server recursively goes down the hierarchy to lookup and return the response to the client. Name server can perform caching to lookup name server at lower level

Q: Recursive vs Iterative?

A: For long distance communiation from the client to the name server, recursive may be better. Also, it depends because we can use caching for iterative as well.

Mobile IP

Nodes in the Internet are phones. This means nodes can move from location to the other, resulting in different IP Addresses. Mobile IP: attaches a home location to each node and if the node moves, it has to register the new IP address with its home server. So when you try to do a lookup or connect to that machine, you first connect to the home server and then get redirected to the IP address of where the node is.

Lecture 10: Clock Synchronization

Logical Clock

If processes only care about event A happens before event B but don’t care about the exact difference, then they can use logical clock. Clock synchronization does not need to be absolute. If two machines do not interact, no need to synchronize them. Processes need to agree on the order in which events occur rather than the time at which they occured.

Event ordering: define a total ordering of all events that occur in a system.

Events in single processor machine are totally ordered

We can use send/receive messages exchanged between processes/machines to order event since messages must be sent before received. We can use transitivity to reason about order of events.

Algorithms for updating logical clocks

- Whenever a local event occurs at machine i, $LC_i = LC_i + 1$

- When machine i wants to send a message, it includes $LC_i$ in the message

- When machine j receives a message from i, if $LC_j < LC_i$ it updates its logical clock as $LC_j = LC_i + 1$ else do nothing

Claim: If we know order of two events A and B, this algorithm ensures that their timestamp will be in order (i.e., if A -> B then ts(A) < ts(B)). If A and B are concurrent, then ts(A) can be <, =, > ts(B)

For example, machine A sends a message to machine B along with its logical clock value 4, and machine B receives this at its logical clock value 3, then we can says that the events happen before logical clock value 4 in machine A occur before the events happens after logical clock value 3 in machine B without clock synchronization.

However, we cannot say about the order of events happen after logical clock 4 in machine A and the events happen before logical clock 3 in machine B. Hence, this is only partial ordering.

Total order

To convert a partial order into a total order, we can append “.” and the process id to the logical clock value in each process, and arbitrarily use the process id to order. For example, an event at time 2 at process i will be stamped 2.i, and an event at time 2 at process j will be stamped 2.j, and if i < j then, 2.i -> 2.j (-> means happens before)

Lecture 11: Total Order and Distributed Snapshots

Total Order Multicast

This is a slightly different problem from event ordering. In lecture 10, we want to have a total order of events in a system. Here we want a total order of the messages delivered by some process. The order of delivered messages is what we care about here.

Assumption:

- No failures

- Point-to-Point FIFO channels (for example: TCP)

Algorithm:

- Multicast messages that have timestamp equal to the logical clock (total ordered logical clock) at the sender

- When receive a message, put it in a queue sorted by its timestamp and send an ack to all. We still have to do all the maintanence of the logical clock: Everytime, we receive a message, if the timestamp of the message is higher than the receiver LC, then set the receiver LC to be the message’s LC + 1.

- If head message in the queue is acked by everyone (i.e, everybody has sent you an ack for that message), deliver.

Implemented at the Middleware layer. One replica will multicast the request, and then some coordination happenning, and when other replicas are ready and know the order is right, they would deliver the request.

Question: Why we need an ack?

To know when to deliver. To wait until we are sure that we aren’t receiving a message with a lower timestamp.

Example:

In a distributed database, if multiple requests are sent to multiple different replicas concurrently, using the total order multicast algorithm, it is guaranteed that all replicas executes all updates in the same order, and then all replicas have the same state.

Still, we are not guaranteed real-world ordering since there is no clock synchronization

Causality:

Lamport’s logical Clock:

- Guarantee that: If A happens before B, then ts(A) < ts(B), but the reverse is not true, ts(A) < ts(B) doesn’t imply A happens before B

- Also need the total order to respect the causal delivery: if send(m) happens before send(n), then deliver(m) happens before deliver(n)

- Also need a time-stamping mechanism s.t. if ts(A) < ts(B), then A happens before B

To achieve the last two requirements, use a vector clock

Vector Clock

Each process maintains a vector clock $V_i$.

$V_i[i]$ is the number of events that have occured at process i.

$V_i[j]$ is the number of events that process i knows have occured at process j.

Update the vector clocks as follow:

- Whenever a local event happens at process i, update $V_i[i]$

- When process i sends a message, piggyback entire vector $V_i$

- When process j receives a message from process i, process j updates $V_j[k] = max(V_j[k], V_i[k])$ for all entries k

- j is told how many events at other process happened before the receipt event

- j assigns $V_j[j] = V_j[j] + 1$ to the receipt event

Exercise: Prove that if V(A) < V(B), then A causally precedes B, and the other way around.

We define V(A) < V(B) iff every element in A is greater to or equal every element in B, and there is at least one element in A that is strictly greater than B.

- Conditions for delivery on message M from $P_i$ to $P_j$, if we have

- $T(M)[i] = V_j[i] + 1$, i.e., this is the next message sent from $P_i$

- $T(M)[k] <= V_j[k]$ for all other k, i.e, $P_j$ has received full context

- then, we can deliver the message!

Using vector clocks, it is now possible to ensure that a message is delivered only if all messages that causually precede it have also been received as well.

Question: Why do we have the above two conditions?

Answer:

First property: We assume here that all messages are broadcasted (i.e everybody receive the messages from everyone), so we don’t want to deliver a message if we know that we miss a previous message that the sender process sent.

Second property: We want to make sure that any messages received by the sender before the message was sent was also received by the receiver!

Question: What if there is a local event happens at project j before j receives the message?

Answer:

Message is still deliver. It’s acceptable to have local events that are concurrent.

Side notes: If two vector clocks are incomparable, it means the events are concurrent, i.e, neither happen before another.

Question: The original algorithm uses Lamport’s logical clocks (LLCs in the following). Let us call it Algorithm 1. Consider an alternative algorithm, called Algorithm 2, where processes only keep simple logical clocks (SLC in the following), which are defined as follows. Each process holds a local SLC. A process increments its SLC by one every time (a) the process takes a local step (b) the process sends a message, or (c) the process receives a message. A total order of events is obtained, like with Lamport’s clocks, by concatenating the SLC of a process with its unique ID. Algorithm 2 uses SLCs instead of LLCs to assign timestamps to each message that is sent. Processes do not keep LLCs in Algorithm 2. Other than this difference, the two algorithms are exactly the same. Describe an execution of Algorithm 2 where the properties of totally-ordered multicast are violated. Argue why using LLCs would avoid the violations.

Answer:

Above is an example where property of totally-ordered multicast is violated. In SLC, event at 2.1 happens before event at 1.2 (because a message must be sent before received), however, the order would be 2.1 -> 1.2.

LLC avoids this violation because whenever a process receive a message, it updates its logical clock as: if $LC_j < LC_i$ it updates its logical clock as $LC_j = LC_i + 1$ else do nothing.

Global State

The global state of a distributed system consists of:

- Local state of each process

- All messages sent but not received

Problem definition: We want to run a distributed application and one of n processes crashes. Rather than killing all the processes and starting from the beginning, we can periodically take snapshots (or checkpoints) of the distributed application to keep a global state and start from the latest snapshot. The snapshot for a global state should be captured in a consistent fashion even without clock synchronization, i.e, Consistent global state or Consistent cut.

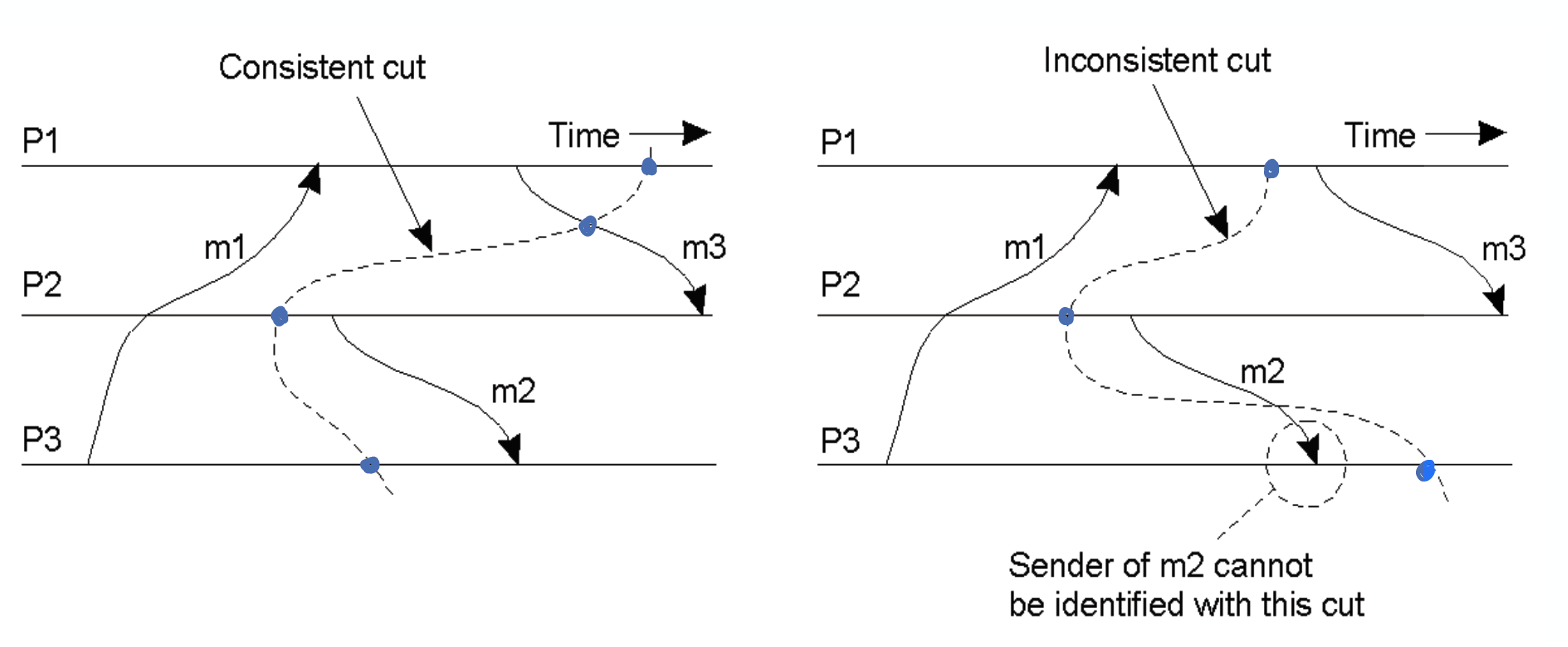

Consistent Cut:

- A possible global state at some point in time

- Can shift relative ordering of concurrent events, i.e., shift events left or right and still receive the same results

Distributed Snapshot Algorithm

Assumptions:

- Point-to-point FIFO channel (e.g. TCP)

- Next instance of algorithm cannot start until previous has terminated

Algorithm:

When a process initiates the algorithm, it will first checkpoint its state and send a marker to every outgoing channel. If a process sees a marker for the first time, it will checkpoint its state, sends markers out and starts saving messages on all other channels. If a process sees a marker for the first time, it will checkpoint its state, sends markers out and start saving messages on all other channels excluding the one with marker. If a process sees a marker for the second time, it will stop saving messages for the channel from which the marker comes from.

Example:

Given two processes A and B.

A sends a message to process B and then initates a snapshot. Due to the FIFO property, when B receives the message from A first and then the marker. B will finish its computation for the message from A and then send its reply. When B checkpoints its state, its state will record that the message to A is sent. The distributed snapshot would record that A already sent the message to B, and B already replied back to A. If A didn’t save incoming message from B, then the result message from B would be lost.

A initiates a snapshot and then sends a message to B. Due to FIFO property, when B first receives the marker and then the message from A. When B receives the marker, it will checkpoint its state and send a marker back to A. B doesn’t need to save message from A because, A sends a message to B after A initiates the snapshot, thus, in the snapshot A saved, its state won’t record that the message to B is sent. So when either A or B crashes, the snapshot stored from A will restart and sends the message to B again! But if B has incoming channels from processes other than A, then B need to save incoming messages from those incoming channels.