(Notes 3) CompSci 677 Distributed System - Editting

Disclaimer: This is my personal class notes for Distributed Operating System course taught at UMass Amherst. All images are taken from the free version of textbook and from slides. Notes contains extracts from textbook and from slides. This notes are for me to review the materials and for you if you are looking to review some concepts.

Lecture 12: Leader Election and Distributed Mutual Exclusion

Problem: Many tasks in the distributed system require one of the processes to act as a coordinator or a master. Example: Berkeley algorithm for clock synchronization. Any process can do the job, but no more than one can do it.

Before we go into details of the leader election algorithm, we have synchrony assumptions: assume channel is point-to-point and there is an upper bound on the time the messages get to the receiver from the sender. The sender sends a message, and the sender knows the time it takes to the receiver is $\Delta t$, and the sender waits for the reply from the receiver. After $2 \Delta t$, if there is no reply, then the sender knows the receiver has failed. Or we can use heartbeat mechanism to detect failure. This assumption doesn’t always hold. There is no way in distributed system that we can know whether a process is slow or death. Synchronous assumptions assume that slow process doesn’t exist!

Bully Algorithm

Assumptions:

- Each process has a unique numerical ID, the ID can be system-specific and can be statically assigned, depends on your distributed system design

- Process knows the IDs and address of all other processes

- Communication is reliable (no message is lost) and synchronous

Assume that, if we just select the process with highest ID as the leader, then everyone knows at the beginning who the leader is. The problem is very trivial. However, this doesn’t take into account fault tolerance: for example, the process with the highest ID fails and everyone else is waiting on it. Also, we also needs to account for the case when the leader fails, several processes may detect this and may initiate an election simultanenously.

Algorithm

- Any process P can initiate an election

- A process initiates election if

- It just recovered from failure or

- It detects that coordinator failed

- 3 message types: Election, OK, Coordinator

- P sends Election messages to all processes with higher IDs and waits for OK messages

- If no OK messages, P becomes coordinator and sends Coordinator messages to all process with lower IDs. Because channels are synchronous, if P receives no OK messages, P knows that none of the processes with higher IDs are alive

- If it receives an OK messagse, it drops out and waits for a Coordinator message

- If a process receives an Election message, it returns an OK and starts an election because by construction

- If a process receives a Coordinator, it treats the sender as the coordinator because by construction, a proccess sends out a Coordinator message only when it makes sure that no other is the coordinator

- Complexity: $O(n^2)$ with $n$ processes

Ring Algorithm

Assumptions:

- Processes have unique IDs and are arranged in a logical ring (overlay)

- Each process knows the IDs and addresses of $f + 1$ successors, where $f$ is the upper bound on faulty nodes. E.g. if at most 1 process can crash, then each process knows at least 2 successors. $f$ is smaller number than $n$

- Synchronous reliable channels

- Process begins election if it just recovered or if it detects that coordinator has failed

Q: What if a process joins while other processes are doing work?

Algorithm:

- Send Election message containing its own process ID to the closest successor that is alive

- Sequentially poll each successor until a live node is found

- At each step along the way, the sender adds its own process ID to the list in the Election message

- Eventually, the message gets back to the initiator, and the initiator picks the node with the highest ID and sends a Coordinator message, which circulate oce again to inform everyone else who the coordinator is

- Multiple elections can happen concurrently (wastes some network bandwidth but does no harm)

Q: Why we need to append the process ID? Can we just keep track of the highest ID so far?

Comparison with Bully Algorithm

Bully algorithm:

- Full knowledge of participants

- Worst case performance: initiator is the node with lowest ID: $O(n^2)$ message

- Best case performance: initiator is the node with highest ID: n-2 messages

Ring algorithm:

- Limited knowledge of participants

- Always $2 (n-1)$ messages

Election in a Wireless Network

Changes in assumption

- Channels are not reliable

- Topology of the network can change

Ideas

Build a spanning tree

Initiator broadcast Election message to all its immediate neighbors. When a node receives an Election message for the first time, it designates the sender as its parent and subsequently broadcast an Election message to all its immediate neighbors execept the parent. Each node then reports to its parent the node with the best capacity. The initiator upon receiving the capacities of all nodes simply picks the one with the highest capacity and broadcast a Coordinator message to declare that node as the leader.

Most capable node is elected as the leader

Election in Large-scale System

There are situations where several nodes should be elected, such as the case of super peers in p2p network.

Requirements

- Normal nodes should be low-latency access to super-peers

- Supper-peers should be evenly distributed across the overlay network

- There should be a pre-defined portion of super-peers relative to the total number od nodes in the overlay network (so that super peers are not overloaded)

- Each super peer should not need to serve more than a fixed number of normal nodes

Algorithm

DHT-based system: to get N super-peers, use keys with the first $k = \log_2(N)$ bits set to the super peer number and the rest to 0

Repulsion: Position node in m-dimensional geometric space, tokens (leaders) have a magnetic force that push each other away. Can place N super peers evenly throughout the overlay.

Distributed Mutual Exclusion

Problem: Distributed system with multiple processes may need to share data or access shared data structures, and we need to use critical sections with mutual exclusion. How do we do this for multiple processes on different machine? Example: synchronization in Java RMI.

Idea: Locking mechanism for a distributed environment, can be centralized or decentralized.

Centralized Mutual Exclusion

One process is elected as coordinator. Every process needs to check with the coordinator before entering the critical section.

To obtain exclusive access: send request, await reply

To release: send release message

Coordinator:

- Receive request: If available and queue empty, send OK; if not queue request

- Receive release: remove the next request from queue and send OK

All locking mechanisms have problems when the process holding the lock crashes.

Pros: fair, simple

Cons: single point of failure, How to detect a dead coordinator? (even if the channel is synchronous, a process cannot distinguish between “lock in use” and a dead coordinator. No response from coordinator in either case), Coordinator is a potential performance bottleneck

Distributed Algorithm

Based on total-order timestamp and total-order multicast

When process k tries to enter critical section:

- Generates a new timestamp ts(k) = ts(k) + 1

- Total-order multicast request(k, ts(k)) to all other n - 1 processes

- Wait until reply(j) or Ok is total-order delievered from each other process j

- Enter critical section

Upon receiving total-order delivering a request message from process k, process j:

- Total-order multicasts reply if no contention

- If j is already in critical section, don’t reply, queue the request

- If j also want to enter critical section, and if ts(k) < ts(j), total-order-multicast reply, else queue.

Q: Can there be starvation?

A: Total-order mutlicast guarantees total-order of delivery of messages. No, there cannot be starvation. At some point, a message will be the message with the lowest timestamp

Properties:

- Fully distributed

- N points of failure! All processes are involved in all decisions. Any overloaded process can become a bottleneck

- Mutual exclusion is guaranteed without deadlock and starvation

Token Ring algorithm

Idea: Have a logical ring on top of the physical network. When the ring is initialized, process $P_0$ is given the token. The token circulates around the ring. Process must wait to get the token to enter critical section. Process pass the token to neighbor once done or if not interested in entering critical section. Guarantee no starvation.

Problem: If token is lost or if the holder of the token crashes then token must be regenerated. It can be difficult to detect if the token is lost if difficult because even if the token has not been circulated, someone may be using it.

Decentralized Algorithm

Idea: Each resource is assumed to be replicated N times. Every replica has its own coordinator for controlling the access by concurrent processes. Whenever a process wants to access the resource, it need to get a majority vote from m > N/2 coordinators. Requests to Coordinator is non-blocking, Coordinator either returns OK or NO. If coordinator crashes, it forget all previous votes. The correctness of the algorithm will be violated if f coordinators crashes and resets, and f >= m - N/2. If permission to access is denied, back off and retry.

Problem: Starvation

Reference: Read more details on page 328 in the textbook for comparison.

Lecture 13: Transaction

Transaction

Transactions are ways to interact with a data store, that can be distributed: for example, have a set of clients that perform read and write operations on a data store, and we want to group all these read and write operations into one group called transactions. Transaction provides atomicity.

ACID properties

- Atomicity: all operations in a transaction are executed or none of them is executed

- Consistency: transaction takes system from one consistent state to another, i.e., transactions need to respect the application-level invariants (for example, no account can go below zero)

- Isolation: Concurrent transactions do not interfere with each other, i.e., transactions are executed as if they are executed sequentially even if they are, in fact, executed concurrently (serializability).

- Durability: Changes are permanent once transaction completes, persisting results of transaction to disk to ensure that if node fails and recovered the result isn’t lost.

Example

Atomicity:

Begin_transaction

if (reserve(NY, Paris) == Full) Abort_transaction

if (reserve(NY, Athen) == Full) Abort_transaction

End_transaction

Nested Transaction

Execute two subtransactions to two different (indepedent) databases.

Example: Suppose we want to book a airplane ticket and a hotel room, if we cannot book either one of them, we don’t want to go. We succeed in booking the airplane, but cannot reserve a hotel room, then we need to go back and unbook the airplane ticket. Still have atomcity and isolation within each subtransaction, but doesn’t have durability because we commit a subtransaction but later on, we may go back and undo it.

Distributed Transaction

Database is distributed across multiple machines, and transaction is splitted into subtransactions, which are executed on this distributed database. Distributed database are coordinated in a way that either all instances commit or none of them commit. We have updates that are tentative, so they must be visible within the scope of the same transaction but must not be visible to other transactions because these updates may be rolled back.

How to store updates that are not yet committed?

- Each transaction gets a private workspace: conceptually, it copies all files and objects in the database before start. But this is expensive

- What we actually do is Copy-on-write: for unmodified block, read from the origin pointer; if we want to modify the block, first copy the original content to a private workspace, then modify, then keep a reference to the new version

- Commit requires making local workspace global

Problem: Even though we use copy-on-write, at some point, we still need to change the main version of the database. When we make the update from the private workspace to the main version of the database, we need to ensure atomicity in this step. What if some failure happens and we only manage to update a subset of the database? Use a write-ahead-log. Prior to updating the database, write updates that are going to be done to a log, force logs to disk, and then apply the updates on to the database! Write ahead logs can help deal with failures (partial update on the database) and also rollback (undo updates when transaction is aborted).

Concurency Control

Goals:

- To allow several transactions to execute simulataneously

- Achieve isolation by ensuring data items are accessed in some order, i.e, serializability: final results should be the same as if each transaction are ran sequentially

- Data are in consistent state

Concurrency control can be implemented in layered-fashion

Serializability: there can be multiple possible interleaving of different transactions. The valid interleavings are those in which there is a sequential order of transactions that yield the same result.

Pessimistic concurrency control: use locks prevent conflicts before accessing the data. Cons: deadlock, overhead of lock request/release

Optimistic concurrency control: each transactions operates in a private workspace, ignore conflicts during execution. Before commits, check if conflict arises, check if files/objects have been changed by committed transactions since they were opened, rollback if conflict

-

Advantages:

- Deadlock free

- No lock management

- If conflict is rare, then optimistic concurrency control works best

-

Disadvantages:

- Everytime, there is a conflict, need to rerun the transaction

- Potential starvation with high rate of conflicts. It’s hard to estimate how many conflicts will be in the application, so pessimistic concurrency control is more popular

locking alone doesn’t ensure serializability

Two-phrase Locking

(Pessimistic concurrency control)

Scheduler acquires all necessary locks in growing phase and release locks in shrinking phase:

- Check if operation on data item x conflicts with existing locks

- If yes, delay transaction. If not, grant the lock on x

- Release the lock when data manager finishes operation on x

- Once lock is released, no further locks can be granted for x. Transaction only releases the lock once it’s done with operation on x

To avoid deadlock, acquire locks in the same order: give a unique id to every variable and make sure that every process acquire the lock in the same ids order

Serializability is guaranteed for transactions schedule following these rules.

Q: How does this satisfy serializability?

Problem: Cascading abort. Release the lock why transaction hasn’t committed yet. If the transaction then aborts, but some other transaction comes in before and already read some updated values from the previous transaction, then those read must also be rolled back!

Strict Two-phase Locking

Release all locks at the same time when the transaction commits.

Disadvantage: Locks are hold longer

Timestamp-based Concurrency Control

(Pessimistic concurrency control)

The serializable order of transactions are consistent with the timestamp of the transactions.

When $T_i$ is about to perform an operation that conflicts with $T_j$: abort $T_i$ if $ts(T_i) < ts(T_j)$

When a transaction aborts, it must restart with a larger timestamp

Read_i(x)

if ts(T_i) < max-wts(x) then abort T_i // check for a read-write conflict

else

perform R_i(x)

max-rts(x) = max(max-rts(x), ts(T_i))

Write_i(x)

// check for a write-write conflict or a read-write conflict

if ts(T_i) < max-rts(x) or ts(T_i) < max-wts(x) then abort T_i

else:

perform W_i(x)

max-wts(x) = ts(T_i)

Lecture 14: Replication and Consistency Models

Replication

Replication in distributed systems involves making redundant copies of resources, while ensuring that all the copies are identical, to improve reliability (if one replica is unavailable or corrupted), fault-tolerance and performance of the system (scale with the size of the distributed system to improve throughput, scale in geographically distributed systems to improve latency).

Data replication: data is replicated on multiple machines

Computation replication: same computing task is replicated on multiple servers

Issue: What happen when one replica is updated and the others are not? Ideally, replication should be hidden from the application

Approach 1: Develop application-level mechanism to keep replication consistent

Approach 2: Middleware handles replication consistency. Because Middleware layer is generic, application need to have some general consistency semantics that works for any replicated object (lose the ability to tailoring specific consistency semantics for the application)

Scalability

Having replications can be both helpful and detrimental to the scalability of the system:

- When we have a low read frequency $R$ and high write frequency $W$, $R < < W$, then incur high overhead to maintain consistency overhead, and this can be wasted because these updates may not even be read. The more replicas, the more consistency overhead.

- Level of consistency can be a factor. Strict consistency models imply more coordination, i.e, higher consistency overhead. Highly scalable system often relies on weak consistency model. Weak consistency may cause different clients accessing different replicas and see different states, so harder to reasoning about the program.

Data-centric Consistency Models

Consistency model represents a contract between processes and the data store: replicas need to coordinate their updates to make the data consistent across replicas. All consistency models attempt to return the results of the last write for a read operation. What do we mean by last write? It depends on the consistency models.

Strict Consistency

Implictly assumes the presence of global clock across all replicas. Reads always return the result of the most recent write. A write is immediately visible to all processes: may need to delay the completion of a write until the update is applied in other replicas. Cost of a write is expensive because it takes time to propagate the update to other replicas.

Sequential Consistency

Weaker than strict consistency

Doesn’t assume global clock/real time

Sequential Consistency: the result of any execution is the same as if the read and write operations by all processes were executed in some sequential order and the operations of each individual process appear in this sequence in the order specified by its program [Lamport, 1979]

Any valid corss-process interleaving is allowed as long as all processes see the same interleaving.

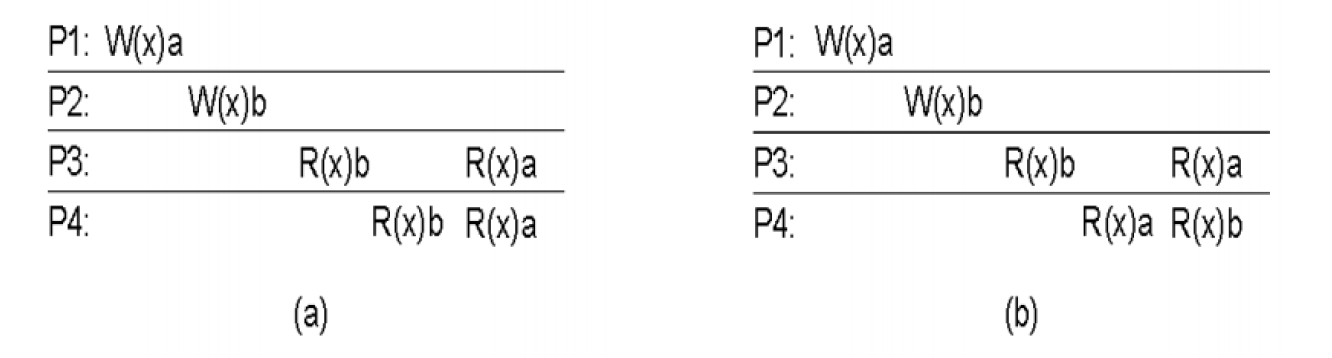

(a) Not satisfy strict consistency because W(x)a happens before in W(x)b in real-time, R(x)a must happen before R(x)b. Satisfy sequential consistency: P3 and P4 both execute R(x)b and R(x)a, then processes agree on the sequential order: W(x)b then W(x)a. This case is not linearizable (see Linearizability).

(b) Not satisfy sequential consistency because P3 and P4 sees different order of W(x)a and W(x)b

No notion of “most recent write” because we can flip the writes order across processes to respect the program order. We can find a sequential order of writes such that all processes read the writes in the same order.

Linearizability

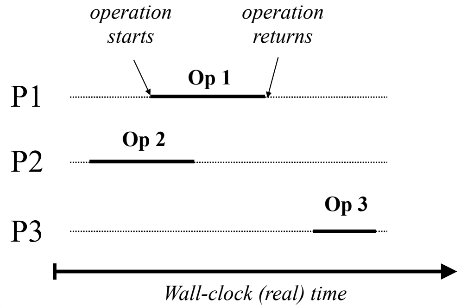

Requires sequential consistency and respect real-time order. How do we define the real-time order? Operations need some time to complete. Operations that overlap in time can be reordered arbitrarily. Operations that don’t overlap need to be ordered according to real-time order.

Order: Op1 - Op2 - Op3 or Op2 - Op1 - Op3

Linearizability is stronger than sequential consistency but still weaker than strict consistency.

Serializability

Consistency in the context of transactions

If we look at database as a single object and at transactions as single operations

Serializability is equivalent to sequential consistency

Strict serializability is equivalent to linearizability

Causal consistency

Causally related writes must be seen by all processes in the same order. Concurrent writes may be seen in different orders in different machines.

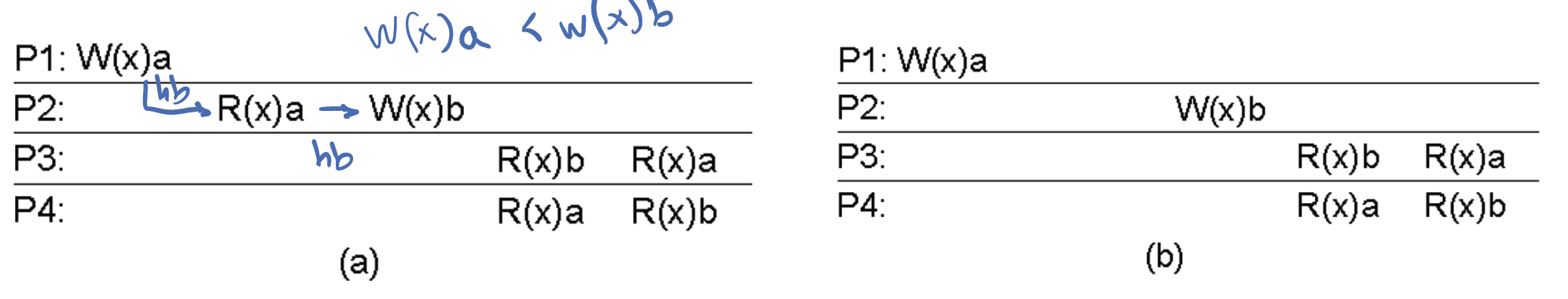

(a) Not causal consistency, because W(x)a happens before W(x)b in a causal relationship, but P3 executes R(x)b before R(x)a

(b) Satisfy causal consistency because W(x)a and W(x)b are concurrent, so any order of read is acceptable

In sequential consistency, all writes must be seen in the same order by all processes. In causal consistency, causally related writes must be seen in the same order. As causally related writes form a subset of all writes, if sequential consistency is fulfilled, then causal consistency is fulfilled.

Eventual Consistency

In absence of updates, all replicas converge towards identical copies. Each replica applies the update immediately and then asynchronously propagate updates to other replicas. Once there is no more update, all replicas converge.

There can be write-write conflicts. Solve conflicts via merging.

Q: How to detect conflicts?

A: Use a vector clock

Example of system use eventual consistency: DynamoDB, DNS,

Q: What happense in case of read-write conflict?

A: Wait for the update to propagate.

Other Models

FIFO Consistency: writes from one process are seen by others in the same order. Writes from different processes may be seen in different orders (even if causally related).

Entry Consistency: Apply only to applications that use lock. Acquire per-item locks to enter critical sections. Upon exit of critical section, send results everywhere.

Lecture 15: Replication Protocol

Replication protocol with no fault-tolerant today.

Replication Implementation

Remote Write, No replication

Clients send Write/Read requests to local server, which forward requests to remote server and return results from remote server to client.

Don’t have issue of consistency but isn’t scalable

By having replication, we trade off between more expensive writes and read performance.

Primary-backup

- Have backup for the data at other servers

- When a write requests is sent to a replica, it is forwarded to the primary server. The primary server applies the update and tells all backup replicas to update, blocking on the write until all replicas acknowledge the update

- Once the update is applied everywhere, acknowledge write completes

Q: Can implement sequential consistent? How and Why? Why not linearizability?

A: When we have only one client, we have sequential consistency. When we have two clients who concurrently write to the same variable, we need to have a FIFO channel (TCP) to guarantee that update requests from primary server to other replicas are sent in order. Because we have the primary server responsible for applying the updates and sending updates to other replicas, this primary server will decide the writes order and guarantee that all writes are in the same order for every replicas. When we have different clients concurrently write to different variables, then we want to have a single primary server for all items to serialize the order of writes.

This protocol doesn’t satisfy linearizability. If we have concurrent writes from different clients, no matter the writes are overlapping or not, the primary server with FIFO channel guarantees the total order of writes. However, different clients can read from different replicas and if the updates is on-going, then reads from different clients may return different results.

Q: Is this protocol fault-tolerant?

A: We can have a timer to check if backup replica is still alive, and we also need to also assume synchronous channel. But if synchronous channel is violated and the acknowledge message from one backup replica is slow, the primary server would assume that that replica is dead and move on and acknowledge that the write completes. Client may come in and read an outdated version from that backup replica.

Local-write protocol

The primary server keeps changing over time.

When a client sends the write/read request to a server (not the primary server for an item), that server move the item to itself and return result operation to client.

It may worth it to transfer the data item to another server, geographically closer to clients to save further computation.

Local-write with replication

Same as local-write protocol, but only transfer the item to another server for write request. The new primary server will tell all backup servers to update on the write.

Read/Write vs Operations (Read/Modify/Write)

So far, when we talk about write, that write will overwrite what we currently have, so our writes aren’t dependent on the object. Operations are more complex than writes: the result of operation and the new state depends both on the operations and the current state of the object. Thus, we need to make sure that operations are applied on the same state. Primary-based protocols support operations: the primary server applies operations on its state and then tells backup servers to perform write updates. Primary performs operations, and other backups only applies the updates, hence this is passive replication.

Active Replication

No (primary + passive backups)

Any replica is allowed to perform operations. Consistency is more complex to achieve because there is primary that serialize the order of operations.

We can use a single sequencer and all replicas performs operations in the same order. But this can cause performance bottleneck!

We can use multiple sequencers and totally-ordered multicast. Sequencers share the load of interacting with servers.

Quorum-Based Protocol

Consider a file is replicated on $N$ servers. Client contact $N_R$ servers for read request and contact $N_W$ servers for write request, and the requirements are that: $N_R + N_W > N$ (protect the read-write conflicts, i.e., read quorum and write quorum intersects in at least one node, i.e, there is at least one server that is contacted for both read and write) and $N_W > N/2$ (protect write-write conflict, i.e., if we have two concurrent writes, they will be aware of each other).

Update:

- Contact $N_W$ servers and read their current version number

- Set the new version as the highest version number you have read + 1

- Write back to $N_W$ servers, which only accept higher versions

Read:

- Contact $N_R$ servers to obtain their version number, read the latest version you can get from the quorum

Properties:

- If we have a write follow by a read, then the read will contact at least one server that have the latest updates

- If we have two writes happenning at the same time, then only one of them will win. The one that win will be determined by the intersection of the two writes' quorums. Write with higher version number is more recent. By having intersection of writes' quorums, we can totally order the writes

- Able to come up with more flexible trade off between the cost of writing and the cost of reading

- We aren’t considering fault-tolerance for this protocol yet!

Epidemic Protocol

Achieve eventual consistency

Even contacting a majority of the servers for writes can be expensive/not available.

Infective replica: replica with an update and is willing the spread the update

Susceptible replica: replica that is not yet updated

Two most common ways to spread an epidemic:

- Anti-entropy: Server P picks server Q at random and exchanges updates. Three possibilites: push updates, pull updates, both push and pull updates.

- Rumor Mongering: Whenever receiving an update, P tries to push updates to random Q. If Q already received the update, stop spreading with probability $1/k$. Analogous to “hot” gossip items spreading quickly. Doesn’t guarantee that all replicas receive updates

Epidemic protocol becomes tricky when we’re removing data because we cannot distinguish between the data is already deleted or if the data is missing. Solution: death certificates - treat deletes as updates and spread a death certificate, and eventually clean up dormant death certificates.

Caching

Client replicates server data

Example: CDN, Web Caching

Problems: Server pushes updates vs client pulls updates, or Send each update vs invalidate the cache.